CNN) -- James Hoyt delivered mail in rural Iowa for more than 30 years. Yet Hoyt had long kept a secret from most of those who knew him best: He was one of the four U.S. soldiers to first see Germany's Buchenwald concentration camp.

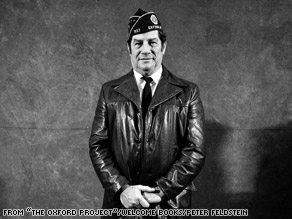

James Hoyt Sr. was one of the four U.S. soldiers to first find the Buchenwald concentration camp.

Hoyt died Monday at his home in Oxford, Iowa, a town of about 700 people where he had lived his entire life. He was 83.

His funeral was Thursday at St. Mary's Catholic Church in Oxford, with about 100 people in attendance. The Rev. Edmond Dunn officiated and recalled time he spent with Hoyt and his wife.

"I used to go over to have lunch with Doris and Jim, and I would sit across from Jim at the kitchen table and think, 'Before me is a true American hero,' " he said.

Hoyt had rarely spoken about that day in 1945, but he recently opened up to a journalist.

"There were thousands of bodies piled high. I saw hearts that had been taken from live people in medical experiments," Hoyt told author Stephen Bloom in a soon-to-be-published book called "The Oxford Project."

"They said a wife of one of the SS officers -- they called her the Bitch of Buchenwald -- saw a tattoo she liked on the arm of a prisoner, and had the skin made into a lampshade. I saw that." Photo See the horrors of Buchenwald »

Pete Geren, the secretary of the U.S. Army, said the sacrifice Hoyt made for his country so many years ago should never be forgotten.

"It's important that we don't allow ourselves to lose him," Geren told CNN by phone. "It's the memory of heroes like James Hoyt and the memories of what they've done that we must ensure that we keep alive and share with the current generation and future generations.

"Mr. Hoyt, as a young man, saw unspeakable horrors when he was one of the soldiers to discover the Buchenwald concentration camp, and those are experiences as a country and a world we can never forget.

"You think back on a young man 19 years old and to have the experience that he had," Geren said, his voice dissolving before ever finishing his thought.

The discovery of Buchenwald, on April 11, 1945, began the liberation of more than 21,000 prisoners from one of the largest Nazi concentration camps of World War II.

The official U.S. military account of the liberation called the camp "a symbol of the chill-blooded cruelty of the German Nazi state," where thousands of political prisoners were starved and "others were burned, beaten, hung and shot to death."

"There is reason to believe that the prompt arrival of the 6th Armored Division ... on the scene saved many hundreds and perhaps thousands of lives," it said.

As a private first class in the U.S. Army, Hoyt was just 19 when he and his three comrades -- Capt. Frederic Keffer, Tech. Sgt. Herbert Gottschalk and Sgt. Harry Ward -- found Buchenwald in a well-hidden wooded area of eastern Germany. See U.S. military documents detailing the liberation »

Hoyt was driving their M8 armored vehicle.

According to military records, Keffer was the officer in command of the six-wheeled armored vehicle that day. The soldiers were part of the Army's 6th Armored Division near the camp when about 15 SS troopers were captured. It was mid-afternoon.

"At the same time, a group of Russians just escaped from the concentration camp, burst out of the woods attempting to attack the SS men. The Russians were restrained and interrogated," Maj. Gen. R.W. Grow, the American commander of the 6th Armored Division, wrote in a 1975 letter about the Buchenwald liberation.

Keffer was ordered to take his three comrades and two of the Russian prisoners "as guides to investigate, report and rejoin as rapidly as possible."

"I took this side journey of about 3 km away from our main force because we kept encountering SS guards and prison inmates, and the latter told us of the large camp to the south," Keffer wrote in a letter around the 30th anniversary of the liberation.

"We had been told by our intelligence that we might overrun a large prison camp, but we -- or at least I -- had no idea of either the gigantic size of the camp or of the full extent of the incredible brutality."

Keffer and Gottschalk, who spoke German, entered the camp through a hole in an electric barbed wire fence. Hoyt and Ward initially stayed at the vehicle.

"We were tumultuously greeted by what I was told were 21,000 men, and what an incredible greeting that was," Keffer wrote. "I was picked up by arms and legs, thrown into the air, caught, thrown again, caught, thrown, etc., until I had to stop it. I was getting dizzy.

"How the men found such a surge of strength in their emaciated condition was one of those bodily wonders in which the spirit sometimes overcomes all weaknesses of the flesh. My, but it was a great day!"

Keffer said the prisoners, through an underground system, had already taken control of the camp. The four soldiers notified division command to get medical help and food to the prisoners as soon as possible.

The 6th Armored Division newspaper "Armored Attacker" ran a headline on May 5, 1945: "Four 9th AIB Doughs Find Buchenwald." The article described the discovery as "the worst concentration camp yet to be uncovered by west wall troops."

Hoyt, a Bronze Star recipient and veteran of the Battle of the Bulge, was the last of the four original liberators to die.

Born May 16, 1925, to a railroad worker and a schoolteacher, James Francis Hoyt Sr. returned to his Iowa hometown after the war and largely kept quiet about the atrocities he saw. He and Doris married in 1949 and had six children. "She's the love of my life," he said.

He met Bloom, a journalism professor at the University of Iowa, in recent years and began telling him his story.

Even 63 years after the liberation, Hoyt suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder and attended a weekly group therapy session at a Veterans Affairs facility.

"Seeing these things, it changes you. I was a kid," he said. "Des Moines had been the furthest I'd ever been from home. I still have horrific dreams. Usually someone needs help and I can't help them. I'm in a situation where I'm trapped and I can't get out."

Hoyt was invited to attend the 50th anniversary of the liberation, but he declined. "I didn't want to bring back those memories."

"Thinking back, I would have pushed to be a psychologist -- if for no other reason than to understand myself better."

The military documents detailing Hoyt's involvement in the Buchenwald liberation were discovered in a box in an archive at the The Center for Military History this week after a CNN query.

It was fitting for the humble Iowan. Hoyt listed his greatest achievement not as a Buchenwald liberator, but as spelling bee champ of Johnson County in 1939, when he was in eighth grade. "I still remember the word I spelled correctly: 'archive,' " he said.

The story of James Hoyt -- mail carrier, spelling bee champ and American hero -- has now been archived for history. Sacrifices like his were something his commander once said future generations should never forget.

"Memories of evil get erased, for life must go on, and new generations cannot be locked in the past. But they would do well to remember the past," Keffer wrote.

At Hoyt's graveside Thursday, a 12-veteran color guard gave him a traditional 21-gun salute. Hoyt's casket was draped with the American flag, and that flag was folded, as is tradition, 12 times.

Retired Gen. Robert Sentman gave the flag to Doris Hoyt. Sentman had earlier told mourners about the Buchenwald liberation.

"When the prisoners saw Jim, they picked him up and threw him in the air, that's how happy they were after seeing such horrors. Prisoners had been hung from hooks to die. He saw a lampshade made from a prisoner's tattoo. Jim carried those horrors with him forever. He never got what he had seen out of his mind. If you ever wondered about Jim, think about what he saw."

"When you were discharged, no one really gave a hoot about you. It was difficult for a compassionate person like Jim to forget what he saw. He was a hero."

Photos of the horror of Buchenwald

http://www.cnn.com/2008/US/08/14/buchenwal...tml#cnnSTCPhoto