Account from Edwin N. Blasingim, First Sergeant, 160 Engineer Combat Battalion, Company B, as told to his son.

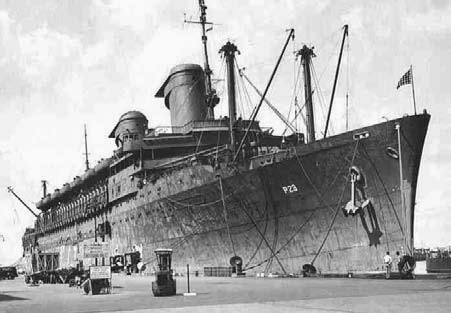

The 160 Engineer Combat Battalion completed overseas training at Fort Rucker in southern Alabama and rode a train to Camp Miles Standish on the south side of Boston, it was June of 1944. After a couple of weeks at Camp Miles Standish they boarded a train for the short ride to Boston Harbor and the U.S.S. West Point, a troop ship converted from the luxury liner S.S. America. It was a short walk from the train to the gangplank but the gangplank was long and steep. Dad didn't think he was going to make it up to the ship with all of his gear. Once on the ship they went to rooms below deck, each man stuffed his gear into a bunk and climbed in with it. Dad remembers how homesick he was on that trip. While he was in the states he often had an opportunity for a visitor or maybe a short leave, but now he was away and not coming home until the war ended, or maybe not ever.

The West Point, nicknamed " The Gray Ghost " was a fast ship and traveled without escort. It sailed at 22-24 knots, full power speed, and set a zig-zag course that made it difficult to catch or intercept.The U.S.S. West Point served all over the world and it made five consecutive round trips from the United States to Europe carrying troops in 1944. The 160th was on the first of these trips. They left Boston Harbor on June 27,1944 with 7,706 men and a crew of 760. The 159 Engineer Combat Battalion was among the passengers on that trip.

The U.S.S. West Point was not a cargo ship but it carried a tremendous amount of mail on the lower decks and cargo holds. Sailing was rough, sea sickness was a nuisance but not a major problem. When you were eating you had to hold on to your food or it could slide off of the table. Dad's usual beverage was coffee, from a tin cup. Guard duty was a regular activity, the soldiers guarded men and equipment in short shifts. The bow of the boat was off limits but some guard posts included a pass to the bow. Dad said that when he was out there the swells were huge, dwarfing the ship. The bow would rise and fall sending waves over the bow deck.

The U.S.S. West Point crossed the North Atlantic and sailed up the Dirth of Clyde to it's destination at Green Rock, near Glasgow, Scotland. It was night but not very dark with the long summer days and as far north as they were.The ship, Scotland and England were totally blacked out. It was July 3,1944. The 160th disembarked and boarded a train that took them south to their camp at Blithfield Hall Manor Grounds near Rugeley, England, about eighty miles northwest of London. Disembarking, loading on the train, the train trip and getting settled in their new temporary home took a day and it was midnight on the Fourth of July before they were properly fed and had a place to sleep.

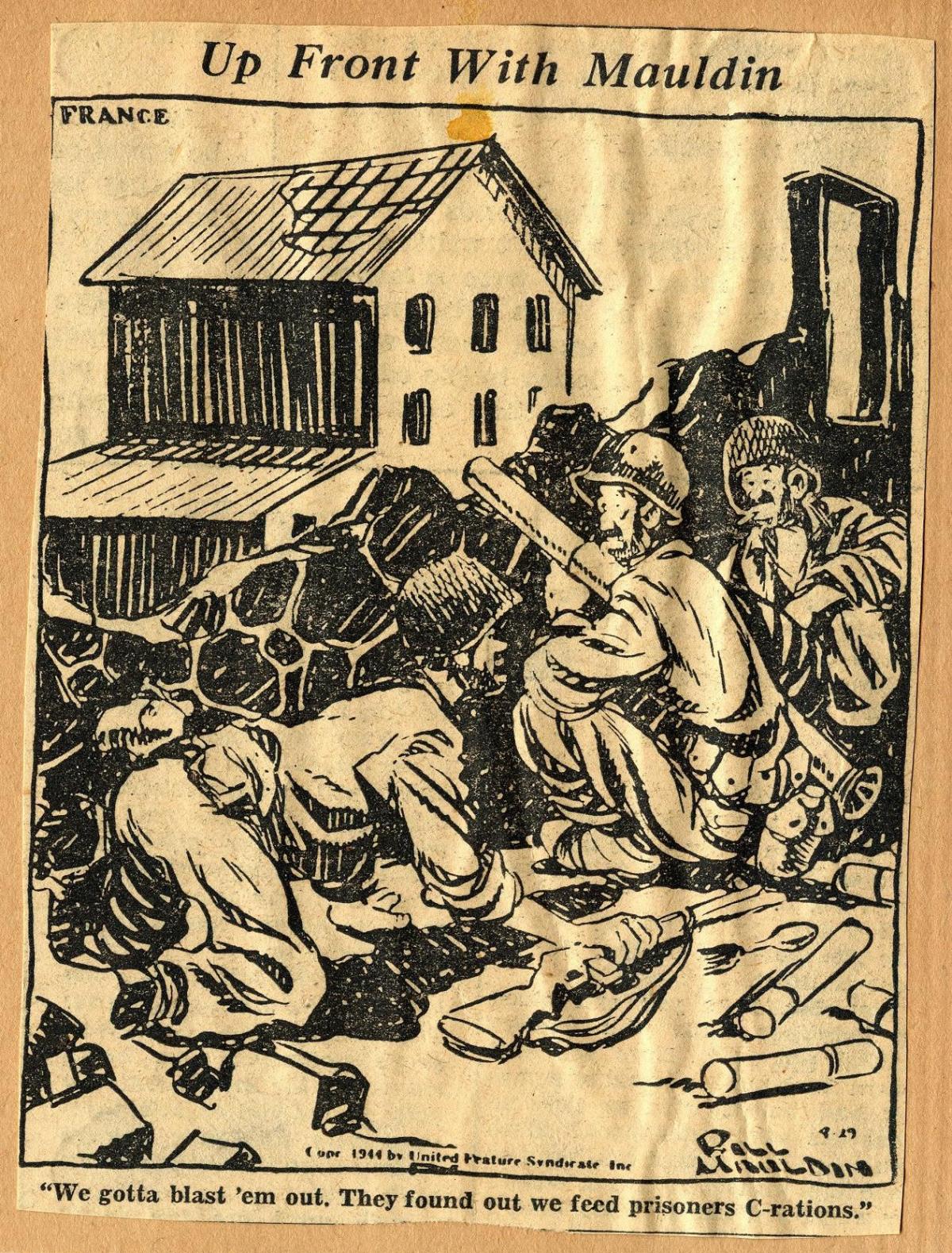

The 160th stayed at Blithfield Hall Manor Grounds for about one month. While they were there they stayed in shape and trained, they did a lot of foot work. They marched the roads and passed through many small towns in the English countryside. The roads were not well paved and the cars were very strange. They went on many hikes through the woods with light packs and they convoyed often, practice for their upcoming adventures in France and Germany. English food was not very appealing and Dad ate G.I. food mostly. A common meal was C-rations boiled in a large pot still in the cans.

When men and equipment were ready the 160th boarded a train to the port of Southampton on the southern coast of England where they boarded a ship that took them across the channel to Normandy.

Camp Miles Standish troop train

U.S.S. West Point

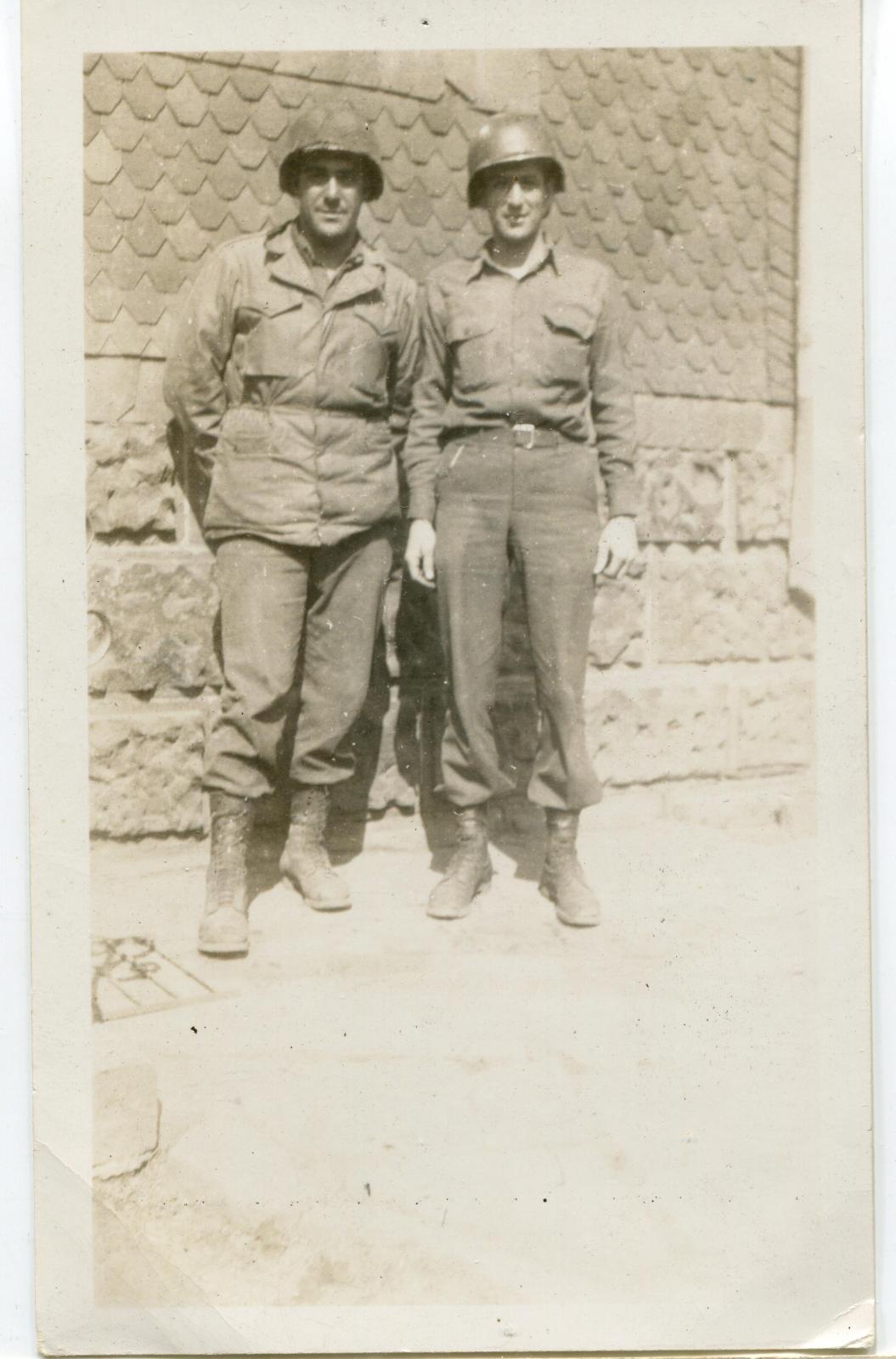

Glen Blasingim