This heartwarming (and tear-jerking) story was found in the June 2009 issue of Reader's Digest. The story begins in June of 1944...

=============

A New World

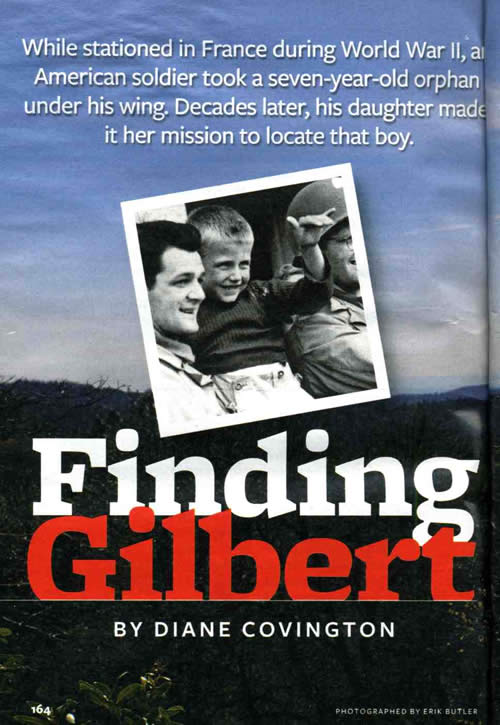

Gilbert Desclos sat in the tall grass on the cliff above Omaha Beach and shivered in the sea air. The sun rose over the trees as he hugged his bony knees tight to his chest and pulled his worn wool sweater around him.

Ever since the arrival of les Américains, his world had changed. Overnight, a military camp had sprung to life on the empty field just below his home in Normandy. For seven-year-old Gilbert, an orphan, it was a boy's dream. His caretaker, Mrs. Bisson, had to drag him in at night.

Diane Covington

Photographed by Erik Butler

Diane Covington, the author, near her home in Nevada City, California, grew up hearing about Gilbert.

Now he watched, wide-eyed, as jeeps roared up the road and men in white caps scurried about, emptying trucks loaded with guns, ammunition, food, and giant duffel bags. He yawned as the smell of bacon, eggs, coffee, and toast wafted up from a massive tent. He tilted his small head back, breathing in the aromas. His stomach growled.

Donald K. Johnson, a lieutenant in the Seabees, the U.S. Navy's Construction Battalion, held a clipboard and checked off the morning's accomplishments. The infirmary tent was complete; now the medics and doctors had a decent place to treat soldiers. The showers worked.

Johnson and his men had been busy since dawn, and it was now noon. He dismissed them, then took a moment and touched the breast pocket that held the photo of his wife and two young sons. It had been more than a year since he'd seen them.

When the lieutenant turned to go, he spied something in the tall grass on the hill. Was that a child? He waved. A small hand waved back. Johnson beckoned. There was a moment of hesitation, then the boy, barely taller than the grass, made his way down. Johnson knelt to look into the child's thin face.

He tried out his high school French: "Comment t'appelles-tu?"

The boy's sparkly blue eyes shone. "Gilbert," he said.

Johnson shook his hand. This little guy looked like he could use a good meal, and the camp had more than enough food. In his halting French, he invited Gilbert to have lunch. When the boy nodded, Johnson lifted him onto his hip, as he might've done with one of his own sons, and headed for the mess tent.

Inside, dozens of young soldiers ate, talked, and clanged their cutlery. Gilbert's eyes grew wide. Johnson piled two plates high with roast beef, potatoes, carrots and peas, freshly baked bread, and apple pie.

The men at the officers table smiled and made room for the two of them. Gilbert took small bites and, chewing slowly, ate everything on his plate. Johnson patted his head: "Très bien!" Gilbert smiled.

After lunch, Johnson held Gilbert's hand, and they walked into the June sunlight. He knelt beside the boy and explained that he had to go back to work. Gilbert nodded and ran back up the path to the tall grass, turning around to wave.

At 1800 hours, as Johnson was again heading for the mess tent, he saw Gilbert sitting in the same spot. He motioned, and Gilbert ran to him.

Dinner was fried chicken, mashed potatoes, corn, biscuits, and chocolate cake. Johnson again filled two plates, but Gilbert didn't eat as much as he had at lunch; it was clear that the boy wasn't used to so much food. But he sat close to Johnson and smiled his shy smile, taking big breaths between bites, as if willing himself to eat as much as he could.

After dinner, Johnson knelt close to Gilbert. "Bonsoir," he said. "A demain," till tomorrow. He watched the boy walk up the path and out of sight.

A New Friend

From that day on, Gilbert ate with Johnson, three meals a day, soon filling out from all the rich food. The other soldiers didn't mind; in fact, the boy helped ease their homesickness. Gilbert giggled when Johnson carried him around on his shoulders and soon began riding along in the jeep down to the beach, where Johnson supervised the unloading of ships. When Johnson oversaw construction projects in the camp, Gilbert tagged along. If Johnson left camp with his crew to rebuild a road or a blown-out bridge, Gilbert waited for his return.

As the summer of 1944 passed, Johnson's French improved, and Gilbert learned to say hello, goodbye, thank you, jeep, ship, and ice cream. He could also say Lieutenant Johnson.

In mid-October, when Johnson received orders to leave France, he drove to the local authorities in Caen to make some inquiries. He discovered that Gilbert had been abandoned at birth and had no living relatives. But when he asked if he could adopt him, the answer was firm: no.

My Father

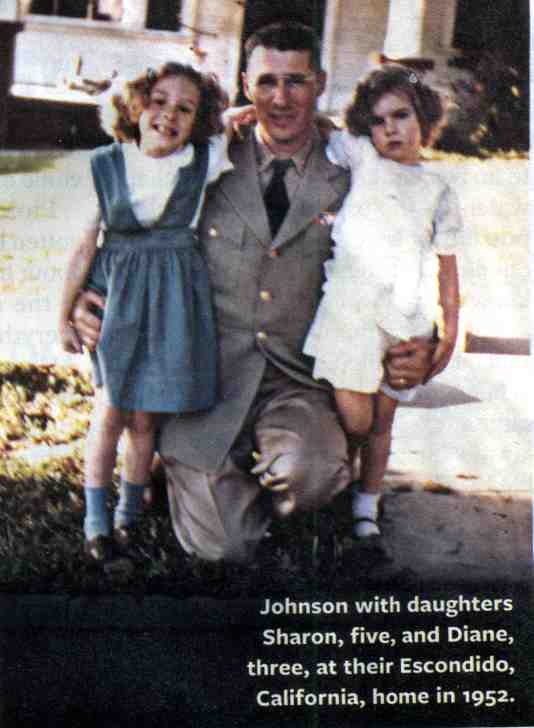

Lieutenant Johnson was my father. Stories about the young boy and wartime France were an element of my childhood, as constant as the roar of Dad's motorcycle as he rolled in each evening at 5:45 after his commute from San Diego, where he worked as a civil engineer for the Navy.

At 6 p.m. sharp, my family gathered around the yellow Formica table that took up most of our small kitchen. Dad and Mom sat on each end, my sister across from me, our older brothers next to us.

Dad looked straitlaced in his short-sleeved white shirt, skinny tie, and plastic pocket liner holding a pen, a notebook, and sometimes a slide rule. But his eyes told you he was kind, funny, a bit mischievous. His stories made me laugh, and when he described his time in France, I could picture it all: the French countryside, the huge Navy ships, and Gilbert Desclos.

Dad always said Gilbert's name with a kind of reverence and the way the French would, with a soft g sound.

I knew he had tried to adopt Gilbert and bring him home. I thought about that sometimes, wondering what it would have been like to have another older brother at the dinner table.

As I grew up, Dad's stories seemed to belong more and more to my childhood, put away with my dolls and coloring books. After I married and had my own family, Dad visited Europe again, stopping in Paris. He told me how he tried to find Gilbert's name in the phone book but couldn't. I remember how his shoulders slumped and his head hung down as he told me about his failure.

In my father's old age, when he could no longer walk and had lost his eyesight, I would sit with him as he talked about his life. When he spoke about France, his eyes shone. They glistened with tears when he mentioned Gilbert, pronouncing his name with that special softness. I stroked his fragile hand, wishing there were something I could do.

Searching for the Past

After Dad died, in 1991, I wanted to learn more about World War II. I traveled to France in 1993 to tour the beaches and write about the 50th anniversary of the D-day invasion. I stood on the cliffs above Omaha Beach, now the site of the American cemetery where nearly 10,000 U.S. soldiers are buried. The air stung my face as I wiped away tears, remembering Dad, wishing I could ask him more questions.

In my article for my local California newspaper, I mentioned Gilbert Desclos. The press attaché at the French consulate in San Francisco read the story and contacted me. Learning that I was going back to Normandy to accept a medal in Dad's honor, she insisted I try to find Gilbert: "The French don't move around as Americans do. He's probably still nearby."

After the medal ceremony, I placed an ad in the local paper. Thinking it would take months, if not years, to find Gilbert, I listed my address in California, then left on a tour around France with Heather, my teenage daughter.

The next morning, Gilbert Desclos, reading his newspaper, wept when he saw my father's name. He called the paper and learned I'd left the area, so he wrote to my home address. My sister, collecting my mail, recognized the name, ran to a friend's, and faxed it back to France. I received it the night before Heather and I were to travel back to Paris and then home.

I called Gilbert and, stammering through my emotions, arranged a place to meet him that evening. As my daughter and I sat at a sidewalk café in Caen, waiting for Gilbert and his wife to arrive, I fidgeted in my metal chair, watching the passing faces. Could I possibly be meeting the boy from my childhood stories? And how would I know him?

Then a trim, well-dressed man walked up, smiled, and said my name. When I looked into his eyes, I saw the same expression of kindness that Dad always had; Gilbert actually resembled Dad somehow.

At his home, after dinner, Gilbert uncorked a dusty bottle of Calvados. As we sipped the apple brandy and talked, I realized that all the years of studying French vocabulary and irregular verbs had prepared me for this moment.

He asked questions about Dad, about our lives, about how Dad had died. He told me how he'd struggled after Dad left France, living in an orphanage, lonely and sad—but that in his teens, a sweet woman had brought him to live with her family. Nourished by those years of love and caring, he went on to join the military, find a good job, and marry his wife, Huguette. Together, they raised their daughter, Cathy.

But he had never forgotten Dad. He had always insisted to Huguette, Cathy, and later his two grandsons that he had a family in America who would come and find him one day.

I told him that Dad had never forgotten him either—that he had talked about him for the rest of his life, even at the end. I could tell that meant everything to Gilbert.

He told me the same stories my father had told, but from a child's perspective: his fascination with the military camp, the delicious food, Dad's gentleness. Remembering the lieutenant's arms around him, he wept again. We sat together, silent and moved, missing the father who had loved us both.

When Gilbert Said Goodbye

Gilbert took a gulp of his Calvados and told me his version of the October day in 1944 when he and Dad said goodbye on Omaha Beach.

Dad held him close. Gilbert hung on tight, burying his head in Dad's thick, wool Navy coat. Cold October winds whipped the sand around them as men rushed by, carrying their heavy seabags on their shoulders, excited to be going home.

"Do you want to come with me to America?" Dad asked.

"Oui," Gilbert murmured.

They boarded the ship. The captain, who'd been watching, shook his head. "Johnson, off the record, if you're caught, I know nothing about this." Dad nodded, shifting Gilbert's weight on his hip.

But within the hour, a storm raged. Twenty-foot waves lashed the hull of the ship. There was no way the boat could cross the English Channel until the storm had subsided.

As the sun set, the wind slackened and sailors prepared for departure. Moments before the ship was to sail, French gendarmes pulled up on the beach, demanding to speak with the captain; a Mrs. Bisson had reported that her ward had not returned home, and they were looking for him.

As Gilbert remembers it, the captain called for Lieutenant Johnson. There was a long, strained pause. The lieutenant appeared at the top of the gangplank, holding Gilbert in his arms. Gilbert sobbed and clung to him. "Non!" he wailed. "Non!" The gendarmes had to pull him away. The ship sailed without the boy, whom Mrs. Bisson placed in an orphanage the same day.

Waiting for the News

Gilbert put the cork in the Calvados bottle. "Your father said he would come back for me. I have been waiting 50 years for some word from him."

We sat in awkward silence until Gilbert's daughter asked, "Why didn't he? Why didn't he come back?"

I couldn't think of what to say in English, let alone French. Then Cathy said softly, "Le destin." It was Gilbert's destiny to stay in France and have his family and his life there.

As we said goodnight, Gilbert took my hand. "I always knew that I would hear from your father, that someone would come," he said. "Thank you."

I didn't sleep that night, picturing the goodbye on that desolate beach, imagining the police pulling a part of Dad's heart away. And how—why—had Dad carried that secret for the rest of his life? Was he ashamed that he hadn't fulfilled his promise? And why hadn't I helped Dad find Gilbert before he died?

As the clock ticked on the bedside table, I realized I would not find answers from the past. But we could go forward from here.

Keeping in Touch

For the next two years, Gilbert and I wrote, phoned, and e-mailed. In 1996, my mother, my sister, Heather, and I traveled to France for a celebration that received coverage in the same newspaper I'd used to find Gilbert.

A year later, the Desclos family came to America, welcomed by 40 members of the Johnson clan, spanning four generations. At dinner one night, Gilbert read aloud a letter he'd written for the occasion, as I translated into English. He shared memories of my father and told us what it meant to finally come to America. It was a dream, he said, that he had thought would remain a dream.

Other relatives and I returned to France several times through the years. Then, a few months before my planned visit last January, Gilbert was diagnosed with liver cancer. He died four days before my arrival.

I made it in time for his funeral. In his tiny village in Normandy, bells tolled as relatives and friends braved the cold to fill the church. The tricolor French flag draped his coffin, carried by an honor guard of fellow veterans.

I sat with Gilbert's family in the front pew and listened to the tributes to his life. During the service, the priest asked me to place on the coffin a photo of my father and one of Gilbert from 1944 together in one frame.

As candlelight flickered on the faces in the photographs and music echoed off the walls of the old church, I realized that Cathy was right: It was le destin that the naval officer and the little boy had found each other and destiny that they'd gone their separate ways. But it was also destiny, I knew now, that had brought them back together.

The fourth photo shows the two families with Diane seated center, and Gilbert behind her.

Proud Daughter of Walter (Monday) Poniedzialek

540th Engineer Combat Regiment, 2833rd Bn, H&S Co, 4th Platoon

There's "No Bridge Too Far"